Sexual Difference: The Path to Generative Communion

Alberto Frigerio

According to the philosopher and psychoanalyst Luce Irigaray, sexual difference is the burning issue of the day: “Sexual difference is one of the problems, if not the problem, that our era has to consider. Every epoch, according to Heidegger, has one thing to consider. Only one. Sexual difference is probably that of our time.”[1]

The sexual revolution[2] that exploded in the 1960s initiated a process of de-stigmatising non-marital sex in all its variations, effecting a progressive and radical emancipation of sexuality from traditional behavioural norms.[3] In particular, the wide proliferation throughout society of identities that go beyond the binary male-female framework, their promotion at a political and legal level and their facilitation by the endless technological possibilities for manipulating the body, all seem to forebode a limitless redefinition of human sexuality. For this reason, some speak of an age of unisex,[4] where everyone is to be considered more or less male or female to different and gradual extents, these being subject to change over time.

On the other hand, the issue of difference between male and female cannot be too easily dismissed as a purely cultural artifice, if only because of the sexual nature of human reproduction, which is the basis of the binary nature of the sexes.[5] At a biological level, sexual difference is confirmed by the anatomical-physiological development of the subject, which begins with the chromosomes, extends to the gonads and genitalia,[6] and also affects brain structure,[7] thus impacting on all aspects of human health.[8]

The impossibility of eliminating sexual difference is proven by psychological research, which reveals the existence of certain characteristic traits of the male and female sexes. These remain constant throughout each age and culture[9]: males are more enterprising and aggressive, females are more inclined to empathy and emotional care.[10] The sexual difference is confirmed by social psychology’s study of parental roles, which reveals the existence of a paternal ethical code and a maternal affective code. These are only partly superimposable and interchangeable.[11] It is also confirmed by psychoanalytical studies of sexuation. These reveal the mutually-supplementary nature of the male and female sexes, in which there are two quantitatively different ways of inscribing the phallic function (tout in men, pas-toute in women), leading to two different forms of enjoyment (phallic in men, Other in women).[12]

The biological and psychological sciences therefore attest to the existence of difference between male and female. What is needed now is not continually to repeat this as if it were an obvious truism, but a philosophical and theological reflection in order to develop the necessary conceptual tools for demonstrating its anthropological meaning.

1. Philosophical Investigation

The two best known and most elaborated paradigms of human sexuality are the Anglo-Saxon theory of gender, which advocates sexual indifference and aims to subvert the traditional view and practice of sexuality[13]; and the continental view of sexual difference, which considers sexual difference as an original and constitutive fact of the human being and seeks to understand it beyond traditional stereotypes.[14]

Gender theory is a composite set of theories aimed at de-naturalising human sexuality in favour of a purely cultural interpretation. The research conducted by gender studies has made it possible to review multiple cultural representations of the masculine and feminine, which change with time and place. In this sense, masculinity and femininity appear to have no constants, and sexual difference seems to take on as many meanings as there are cultures and, indeed, individuals. Gender studies thus seem to endorse gender theory’s undifferentiated reading of the sexes, which replaces the concept of sex with that of gender. Some gender theorists propose a division of the sex/gender system into two separate spheres, in order to guarantee the independence of the cultural sphere from the natural one.[15] Others invite us to consider sex as a cultural construction that rests on the performative power of language, in order to establish the dependence of the natural sphere on the cultural one.[16]

Gender theory, itself inherently post-structuralist, has the merit of highlighting the effect of social discourse on the definition of masculinity and femininity, and the importance of language in the development of identity. It thus overcomes a naturalistic view of sexuality, which deduces masculine and feminine predicates ‘from above’ on the basis of the male or female body. On the other hand, the influence of the speaker on the living is understood in an almost unilateral sense and gives language the magical power to create the real.[17] According to the philosopher Sylviane Agacinski, post-structuralism does not see the human being as a living being endowed with language; rather, it subordinates the living being to language, according to a dualistic, spiritualistic and logocentric anthropological vision.[18]

Indeed, a phenomenological-hermeneutic study of corporeality would suggest considering the body as a living reality, and one which contributes to the development of self-identity. The eponym of phenomenology, Edmund Husserl, explained that the body is not only body-object (Körper) but also body-subject (Leib), insofar as it participates in the establishment of personal identity.[19] Paul Ricoeur, who integrated phenomenology with hermeneutics, teaches that the cogito is rooted in the corporeal, insofar as one’s own body is the first form of otherness, and has thus always influenced the subject’s psychic elaboration and their moral life.[20] To pretend that gender is separated from sex, or that gender absorbs sex, is to misunderstand the role that the body plays in the process of gendering, by subjecting it completely to the linguistic dimension and reducing it to a manipulable appendage.

Body and language are interlinked. Language signifies the body, which is in its own turn a reality that is pregnant with meaning: “The logos ‘informs’ the body, it is true. On the other hand, it must also be said that the logos is ‘informed’ by the body.”[21] If human sexuality is not simply an organic datum, neither is it merely a product of culture, insofar as the human body has always possessed a symbolic importance that opens up the dimension of meaning: “The natural (biological) condition is at the same time symbolic.”[22] The inescapable fact of sexual difference serves to generate a multiplicity of meanings that are received and manifested culturally.[23] This is the core assumption at the heart of the paradigm of sexual difference, and it is manifested both in experience of the individual and in that of the couple.

At the level of personal experience, the theorists of sexual difference understand the latter as an inalienable and yet indefinable datum. They refuse to define any constants within masculinity or femininity, for fear of enclosing them in rigid and prefixed schemas.[24] On the other hand, as the philosopher Susy Zanardo points out, sexual difference is an inevitable, though not a determining, reality that also provides a certain orientation and mode of being in the world of men and women. If sexual difference transcends the subject’s own power of expression, this is not cause for us to renounce its meaning. For Zanardo, the root of difference is to be found in the experience of generation, with its differing male and female contributions. The woman brings the other into herself; the female body is a place that receives the other, thus opening up to new life. The man brings himself into the other; his body puts itself into the other and places life into it. This explains why the mother risks devouring the other, while the father risks putting himself before the other.[25]

At the level of the experience of the couple, theorists of sexual difference consider this latter to be the fruit of a process of elaboration within the subject or with those similar to the subject, for fear of defining each sex relative to the other and thus falling into a functionalist vision of complementarity.[26] On the other hand, and as Zanardo points out, sexual difference takes on its meaning in a relational context, especially that of the couple. In this context, the identity of the subjects matures and they prepare both to give themselves and to receive that which they are not and that which they cannot achieve on their own. In Zanardo’s view there is no identity without difference, since identity implies an understanding of oneself as identical to oneself and different from others. The subject cannot find itself without the existence of an other who is different from oneself – especially without the other who is sexually different, because the most radical difference is sexual difference.[27] It is this that makes another human being, who is otherwise equal to oneself, either different from oneself or identifiable with oneself: man or woman. Sexual difference is inscribed in the subject as a limitation, insofar as the other limits the self, and the self realises that it is not everything. However, this limit is not a reason for conflict, as is the case within gender theory, which aims to abolish it in favour of sexual indistinction; nor is it a mere vulnerability, as is the case with the theory of sexual difference, according to which incompleteness is not resolved in the relationship with difference, but is elaborated within oneself and with the similar. Rather, the limit is also a richness insofar as sexual difference opens the subject up to otherness, to another way of being human that is inaccessible to itself. Thus, sexual difference invites the subject to seek the other, without which the self does not exist: “Insofar as it signifies otherness, sexual difference is the place where one learns to desire the other.”[28]

2. Theological investigation

Biology, psychology and philosophy have all attested to the existence of sexual difference and have demonstrated its importance for the life of the individual and of the couple. These now await to be enlightened by Divine Revelation. We will analyse the Genesis creation accounts, re-reading them in the light of the Trinitarian relationship, after which we will offer some theological reflections on the family as the dwelling place of the person and as the womb of society.

The first chapters of Genesis, which are the mature fruit of Israel’s historical experience, have been chosen due to the fact that they constitute a meta-historical aetiology. In other words, they seek to explicate the constitutive content of humanity.[29] The priestly cosmogony of Genesis 1 and the Jahwist cosmogony of Genesis 2 thus outline the divine plan for human love with the following three coordinates: 1. The human being is created in the unity of two different beings: “God created man, male and female he created them” (Gn 1:27); 2. The two are invited to live in communion: “Man shall leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and the two shall become one flesh” (Gn 2:24); 3. Communion enables the two to cooperate with the act of creation: “God blessed them and said to them: be fruitful and multiply” (Gen 1:28). The Book of Genesis thus delineates the physiognomy of human love not only according to a nuptial perspective, which implies the spousal relationship between man and woman, but also according to its orientation towards family life through maternity and paternity. This is expressed by the exegete Patrizio Rota Scalabrini, as follows: “The meeting of the couple constitutes the basis of the relationship of kinship and generation.”[30]

The Genesis accounts of creation, especially the first one, lend themselves to being re-read in the light of the Trinity, thus revealing human love more fully. This is suggested by a number of exegetes who see the Trinity concealed in the doctrine of the imago Dei in Genesis 1: “God said: Let us make man in our image, after our likeness” (Gen 1:26). The intentio auctoris refers to humanity’s ability to enter into a free relationship with God, insofar as the plural is explained as pluralis deliberationis, or in relation to the heavenly court. Thus, the purpose of the individual man and woman is not to be found in themselves or in the other, as if they could complete each other; rather they are characterised by the dialogue they are called to enter into with the Creator. On the other hand, the exegetical principle of the sensus plenior authorises us to interpret the passage in the light of the Trinitarian revelation, which reinterprets the openness of the two to God in the openness of the one to the other.

The creation of the sexed human being (v. 27) and the invitation to multiply (v. 28) suggest “a relationship of similarity between God who creates and man, male and female, who, blessed by Him, procreates.”[31] The analogy between God’s creative action and the procreative action of the two reveals the development of the analogy between the fruitful couple and the Trinity, Who is fully revealed by the proclamation of God as Love (1 Jn 4:8).[32] Therefore, the imago Dei is manifested in individuality as well as in the union between human beings, especially in the relationship of the couple: as God is one and multiple, so His image is individuality and communion.

The Trinitarian doctrine teaches that God is a communion of persons (μια ουσια τρεις υποστασεις = one nature three persons), in which differences are experienced in perfect unity. The Trinitarian differences between the Father, Son and Spirit are rooted in and are a condition for experiencing fruitful communion. In the divine life, the Father generates the Son, and from the Father and the Son proceeds the Spirit, who is the bond (nexus) and the fruit (donum) of their love.

The proclamation of the Triune God illuminates the person, who is fully realised by the exchange of love is realised from, for and with the other[33]; and it illuminates the sexual relationship, in which the original and divine communio personarum shines forth in a singular way. Yves Simoens’ exegesis of Gen 1:26 suggests that, “The differentiation in God, expressed by the first-person plural verb ‘let us’, is followed by the differentiation in the human being: male and female; it constitutes the image and the likeness. One differentiation is not without the other. Communion in God grounds the communion of the couple. God expresses the masculine and the feminine as the masculine and the feminine express God.”[34] In this sense, the effigy of God is fully realised in a sexual polarity that is capable of giving life.[35]

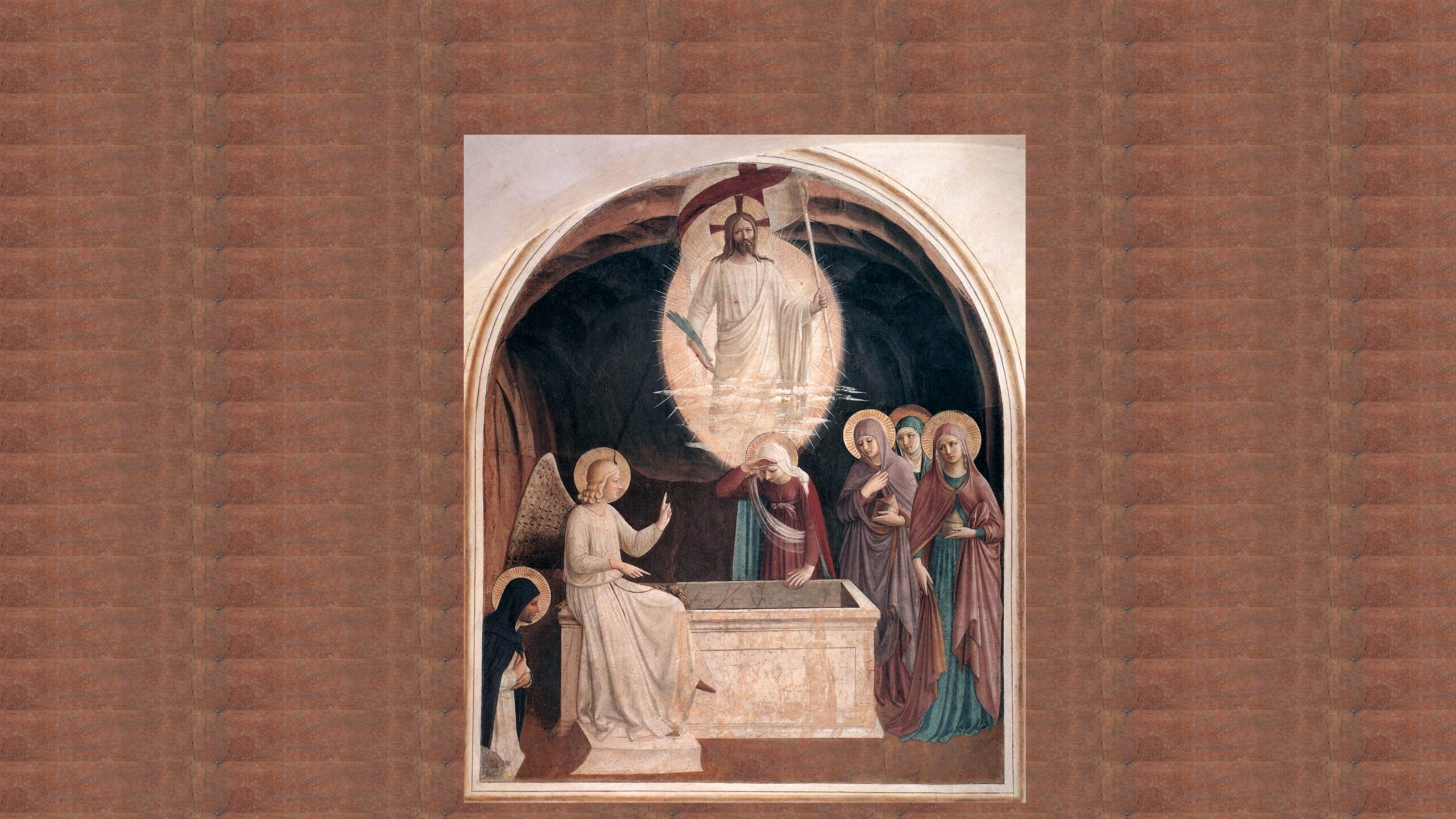

The archetypal accounts of Genesis present sexual difference as a constitutive datum of the human being. They disclose the meaning of human love, in which the person transcends himself in order to find himself in the other, who is the beloved and the fruit of this love. The combined reading of the creation narratives invites us to read sexual difference as a call, addressed to both, to open up to the other (Genesis 2) and to bear fruit with the other (Genesis 1). The perichoresis of the Three in Trinitarian Revelation thus illuminates the correlation between sexual difference, oblation and generativity. In the Trinitarian life, personal differences are paths to fruitful communion; and every other difference, such as sexual difference, arises from the Trinitarian difference as a path to generative union. Cardinal Angelo Scola explains it thus: “Sexual difference, the place where the self, as corpore et anima unus, encounters the objective presence of the other, opens up the possibility of the relationship between the two, revealing its own intrinsic (loving) orientation towards gift. From this exchange between the two there always blossoms a fruit (fruitfulness) […] In the Trinitarian relationships and missions, which culminate in the genesis of the Church Bride by Christ the Bridegroom in the Easter event, we find difference, gift and fruitfulness, that is, the inseparable interweaving of the three constitutive factors of the nuptial mystery.”[36]

The nuptial character of human love, subtended by the Genesis narrative and fully revealed by Trinitarian Revelation, invites us to enucleate the primordial experiences of life, which make up the grammar of family relationships. It is within these that personal identity matures and social construction takes place: in recognising oneself as son or daughter, in being a husband or wife, in becoming father or mother.

The very first identifier of a person is that of being a son or daughter, and this presents itself as an inescapable and fundamental fact. The term ‘nature’ derives from the Greek φύσις, meaning generation, and from its Latin translation natus (past participle of the verb nasci), meaning to be born. The etymology indicates that the experience of being born is universal, implying that the element held in common by all life is that of being generated. The birth-event is emblematic of the human condition, in which freedom is realised above all in receiving oneself.[37]

A human birth is always a grace-filled event, in that no one is self-made and each one receives life. This fact cannot be obscured even if one were to clone a person: the cloned person always presupposes the one who clones. However, human dignity entails the need to be generated by an act of love, since the child can only be received as a gift not in a technical act of production, but in a personal gesture of mutual giving by lovers. For this reason, those practices that separate the procreative event from the unitive act are detrimental to the generative process and injure the filial relationship, even more so when they sever the unity of the biological, obstetrical/gestational and social dimensions of parenthood.[38]

The filial identity is preserved and cultivated in the relationship with the parents. It is this identity that constitutes the first foundation of the call to be a husband or wife, which in turn are orientated to becoming a father or mother, since it is only in receiving oneself that the person learns to give himself. The experience of freedom as a dimension that arises and is nurtured within the relationship with another person then constitutes the source from which the person draws to build and form that communion of persons which is characteristic of the family. On the contrary, the individualist conception of freedom, uprooted from the relationship of sonship, weakens the identity of the subject and his ability to act on behalf of others. This is what the essayist Mary Eberstadt argues, according to whom today’s identity crisis, attested to by the pervasive and divisive theme of identity politics, is primarily due to the great family dispersion connected to the phenomenon of the sexual revolution: the person, outside of basic family relationships, has difficulties in finding his identity and in making a gift of himself.[39]

The person, therefore, is not an autonomous and isolated individual, but a being-in-relationship, whose identity matures in the family relationships of son and daughter, husband and wife, father and mother. Benedict XVI observed this very fact on the occasion of his Christmas greetings to the Roman Curia in December 2012:

“It was noticeable that the Synod repeatedly emphasized the significance, for the transmission of the faith, of the family as the authentic setting in which to hand on the blueprint of human existence. … [T]he question of the family is not just about a particular social construct, but about man himself – about what he is and what it takes to be authentically human. … When such commitment is repudiated, the key figures of human existence likewise vanish: father, mother, child – essential elements of the experience of being human are lost.”[40]

As the Pope Emeritus teaches, family relationships are decisive for the transmission of faith, insofar as they have a religious quality; that is, they manifest God’s closeness, charged with benevolence and gratuitousness.[41] Moreover, family relationships offer a solid contribution to the building up of society, inasmuch as they constitute the privileged environment for the maturation of the person and favour an attitude of generosity and mutual help, loyalty and trust, which forms the basis of civil coexistence.[42]

3. Concluding remarks

The human being, made in the image and likeness of the One God, finds his identity in the communion of persons, of which the family is the paradigm: to be son and daughter in order to become husband and wife and reach the point of being father and mother. The family founded on marriage emblematically expresses the nuptial (communal and generative) nature of love, of which virginity documents the structural origin from the Other and the openness to the Other.[43] In this sense, the family casts light on the truth of man and of God: the family community is an image of Trinitarian communion, in which the person understands that he or she is a beloved son or daughter, learns to share love as brother and sister, discovers that he or she is called to give himself or herself as husband or wife and to generate as father or mother.[44] As Eberstadt points out, it is for this reason that the family reality is intrinsically linked to the religious dimension, with which it collaborates for the maturation of the whole of society: “Family and faith are the invisible double helix of society—two spirals that when linked to one another, can effectively reproduce, but whose strength and momentum depend on one another.”[45]

Translated by Stefan Kaminski

-

Luce Irigaray, Éthique de la différence sexuelle, Minuit, Paris 1984, 13. ↑

-

Fabio Giardini, La rivoluzione sessuale, Edizioni Paoline, Milano 1974. Conor Sweeney, “Rivoluzione sessuale,” in José Noriega – René and Isabelle Ecochard (eds.), Dizionario su sesso, amore e fecondità, Cantagalli, Siena 2019, 839-844. ↑

-

Mary Eberstadt, Adam and Eve After the Pill. Paradoxes of the Sexual Revolution, Ignatius Press, San Francisco 2012. ↑

-

Anne Fausto-Sterling, Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality, Basic Books, New York 2000, 147. ↑

-

Gabriel José de Carli – Tiago Campos Pereira, ”On Human Parthenogenesis,” in Medical Hypotheses 106 (2017), 57-60. ↑

-

Alfred Jost et al., ”Studies on Sex Differentiation in Mammals,” in Recent Progress in Hormone Research 29 (1973), 1-41. ↑

-

M. M. McCarthy, Sex and the Developing brain [second edition], Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences, 2017, VI. ↑

-

Theresa M. Wizemann and Mary-Lou Pardu, Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health. Does Sex Matter? National Academy of Science, Washington DC 2001. ↑

-

Janet Shibley Hyde, ”Gender similarities and differences,” in Annual Review of Psychology 65 (2014), 373-398. ↑

-

Vanda Zammuner, “Identità di genere e ruoli sessuali,” in Silvia Bonino (ed.), Dizionario di psicologia dello sviluppo, Einaudi, Torino 1994, 339-344. ↑

-

Raffaella Iafrate, ”La figura paterna nelle relazioni familiari e sociali,” in Anthropotes 35 (2019), 251-266. ↑

-

Jacques Lacan, Le Séminaire. Livre XX. Encore (1972-1973), Seuil, Paris 1975, 73s. ↑

-

Laure Bereni, Sébastien Chauvin, Alexandre Jaunait, and Anne Revillard, Introduction aux études sur le genre, De Boeck Supérieur, Bruxelles 2012. ↑

-

Riccardo Fanciullacci,”Il significare della differenza sessuale: per un’introduzione,” in Riccardo Fanciullacci and Susy Zanardo, Donne e uomini. Il significare della differenza, Vita e Pensiero, Milano 2010, 3-59. ↑

-

Gayle Rubin,”The Traffic in Women: Notes on the Political Economy of Sex,” Rayna Reiter (ed.), Toward an Anthropology of Women, Monthly Review Press, New York 1975, 157-210, 159. ↑

-

Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex,” Routledge, New York and London 1993, XV. ↑

-

Camille Paglia, “Free Speech and the Modern Campus,” in Provocations, Pantheon, New York 2018, 369-381, 379. ↑

-

Sylviane Agacinski, Femmes entre sexe et genre, Seuil, Paris 2012, 145-146. ↑

-

Edmund Husserl, Méditations Cartésiennes § 44, Librairie Philosophique J. Varin, Paris 1980. ↑

-

Paul Ricoeur, Soi-même comme un autre, Seuil, Paris 1990, études 10. ↑

-

Carmelo Vigna, “Sulla liquefazione del Gender,” in Carmelo Vigna (ed.), Differenza di genere e differenza sessuale. Un problema di etica di frontiera, Orthotes, Napoli-Salerno 2017, 25-45, 38. ↑

-

Carmelo Vigna, “Prefazione,” in Carmelo Vigna (ed.), Differenza di genere e differenza sessuale. Un problema di etica di frontiera, Orthotes, Napoli-Salerno 2017, 5-9, 5. ↑

-

Sylviane Agacinski, Politique des sexes. Précédé de Mise au point sur la mixité, Seuil, Paris 2001, 57. ↑

-

Françoise Collin, “Différence et différend. La question des femmes en philosophie,” in Françoise Thébaud (ed.), Histoire des femmes en Occident. Le XXe siècle, vol. 5, Plon, Paris 1992, 243-273. ↑

-

Susy Zanardo, ”Gender e differenza sessuale. Un dibattito in corso,” Aggiornamenti sociali 65 (2014), 379-391. ↑

-

Luisa Muraro, “Prima lezione. La rivoluzione simbolica di partire da sé. Le tre ghinee di Virginia Woolf,” in Riccardo Fanciullacci (ed.), Tre lezioni sulla differenza sessuale e altri scritti, Orthotes, Napoli-Salerno 2011, 23-36. ↑

-

Susy Zanardo, ”La questione della differenza sessuale,” Aggiornamenti sociali 66 (2015), 833-844, 843. ↑

-

Susy Zanardo, “Differenza di genere e differenza sessuale,” in Carmelo Vigna (ed.), Differenza di genere e differenza sessuale. Un problema di etica di frontiera, Orthotes, Napoli-Salerno 2017, 13-24, 24. ↑

-

G. Borgonovo, L’eziologia metastorica, Pro Manuscripto, Seveso 2008-2009. ↑

-

Patrizio Rota Scalabrini, “Da principio fu così … Antropologia e teologia della coppia in Genesi,” in Giuseppe Angelini (ed.), Maschio e femmina li creò, Glossa, Milano 2008, 117-149, 144. ↑

-

Régine Hinschberger, ”Image et ressemblance dans la tradition sacerdotale Gn 1,26-28; 5,1-3; 9,6b,” Revue des sciences religieuse 59 (1985), 185-199: 192. ↑

-

Le conclusioni esegetiche richiamate sono state riprese dalla Lettera apostolica Mulieris dignitatem di Giovanni Paolo II, che per il Card. Marc Ouellet è il testo magisteriale più audace sull’imago Dei: Marc Ouellet, Mistero e sacramento dell’amore. Teologia del matrimonio e della famiglia per la nuova evangelizzazione, Cantagalli, Siena 2007, 176. ↑

-

Joseph Ratzinger, Fede, Verità e Tolleranza, Cantagalli, Siena 2003, 263-264. ↑

-

Yves Simoens, Homme et Femme. De la Genèse à l’Apocalypse, Éditions Facultés Jésuites de Paris, Paris 2014, 33. ↑

-

Gianfranco Ravasi, Il racconto del cielo. Le storie, le idee, i personaggi dell’antico testamento, Mondadori, Milano 1995, 38. ↑

-

Angelo Scola, Il Mistero Nuziale. Uomo-Donna. Matrimonio-Famiglia, Marcianum Press, Venezia 2014, 14 e 278. ↑

-

Ferdinand Ulrich, Der Mensch als Anfang: Zur philosophischen Anthropologie der Kindheit, Johannes Verlag, Einsiedeln 1970. ↑

-

Adriano Pessina, ”La generazione dell’inganno. A margine della legge 40,” in Vita e Pensiero 3 (2014), 146-150. ↑

-

Mary Eberstadt, Primal Screams. How the Sexual Revolution created Identity Politics, Templeton Press, West Conshohocken 2019. ↑

-

Benedict XVI, Address of His Holiness Benedict XVI on the Occasion of Christmas Greetings to the Roman Curia, 21 December 2012. ↑

-

Matteo Martino, “Genitori testimoni dell’origine. La qualità religiosa dei legami familiari,” in Maurizio Chiodi – Markus Krienke (eds.), Coscienza, cultura, verità. Omaggio alla teologia morale di Giuseppe Angelini, Glossa, Milano 2019, 309-323. ↑

-

Pierpaolo Donati, La famiglia. Il genoma che fa vivere la società, Rubbettino, Soveria Mannelli 2013. ↑

-

José Granados, Una sola carne en un solo Espíritu. Teología del matrimonio, Palabra, Madrid 2014, 333-357. ↑

-

Livio Melina, Building a Culture of the Family. The Language of Love, St. Paul – Alba House, Staten Island, NY 2011, 3-21. ↑

-

Mary Eberstadt, How the West Really Lost God, Templeton Press, 2013, 22. ↑

Share this article

About Us

The Veritas Amoris Project focuses on the truth of love as a key to understanding the mystery of God, the human person and the world, convinced that this perspective provides an integral and fruitful pastoral approach.