Review: Matthew Levering, Engaging the Doctrine of Marriage, Cascade Books, Oregon 2020

Stefan Kaminski

Matthew Levering’s Engaging the Doctrine of Marriage is the fourth and latest volume in his series, Engaging Doctrine. It follows on from volumes on Revelation, the Holy Spirit and Creation.

Levering’s intention with this series is to present a systematic treatment of the Church’s dogma. Whilst his series builds on the fundamentals of “Scripture as mediated in Tradition, with a central role for the Fathers and the medieval schoolmen”, Levering’s specific concern is to engage each area of dogmatics within its contemporary context[1]. His method is to draw from a selection of particular authors and to allow them to ‘speak’ to each other in their own words. Levering thus aims to develop a dialogue as per the classical method, within the pages of his volume, between advocates of opposing positions in order to draw out more fully the truth of the Church’s doctrine.

The place of the present volume on Marriage within the series reflects, I believe, the author’s overall intention with this volume. From Levering’s own brief sketch of the previous volumes in the preface, the uniting theme that emerges in all three is that of relationship: the place of the Church in mediating God’s revelation to His people (the first volume); the Trinitarian relationship, examined particularly through the Person of the Holy Spirit (the second volume); the relationship between the Triune Creator and His creatures, and in particular with man in His image (the third volume). With the present volume, Levering desires to place the Sacrament of Matrimony firmly in the context of the mystical marriage between God and His people.

The author acknowledges the potential rationale for proceeding with a volume on Jesus Christ, rather than one on marriage, after that on Creation, noting that “before the foundation of the world” God “destined us in love to be his sons through Jesus Christ” (Eph 1:4-5)[2]. However, it is precisely his conviction regarding the nuptial nature of the Old Testament covenants, of the mission of Christ as the Bridegroom and the end of all things at the wedding feast of the Lamb, that motivates the series’ ordering.

The book’s orientation is made clear by the author’s method. Given his centring of the doctrine of marriage upon the mystical marriage of God and creation, Levering approaches earthly marriage in relation to four themes of fundamental doctrine: the relationship of God with His people, humanity’s creation in the image of God, Original Sin, and the Cross of Christ. Following this theological groundwork, the remaining three chapters of the book turn to practicalities around marriage, tackling its purpose, its sacramentality and its place in society.

From the outset it is clear that Levering does not shy away from ‘difficult’ themes within, or objections to, the Christian tradition. On the contrary, he thoroughly delivers his stated objective of clearly presenting opposing positions. The first, Scripturally-focussed chapter, God and His People, presents Christ as the fulfilment of the marriage covenant enunciated in the Old Testament. However, half of the chapter is dedicated to addressing the “abusive” images of God found in the Old Testament; for example, the words of the prophet Nahum: “I am against you, says the Lord of hosts, and will lift up your skirts over your face; and I will let nations look on your nakedness and kingdoms on your shame. I will throw filth at you and treat you with contempt, and make you a spectacle.” Such passages lead the likes of Gerlinde Baumann to assert that “YHWH appears as a rapist”[3]. Levering draws on the interpretations of the Church Fathers, in particular St Jerome, to offer a careful unpicking of each these ‘difficult’ passages in the light of the Church’s (Western and Eastern) tradition of allegorical, typological and tropological reading of parts of the Old Testament. Levering shows how according to St Jerome Nahum’s words, for example, constitute a reverse allegory. He makes space for the insights of historical-critical scholarship to explain the actions described in such passages, in the ritual practices of the time surrounding widows and divorcees. Levering thus demonstrates how such passages are indeed intended to provoke repentance in the female figure, who is always understood as a metaphor for the “generative mother” that is Israel collectively[4].

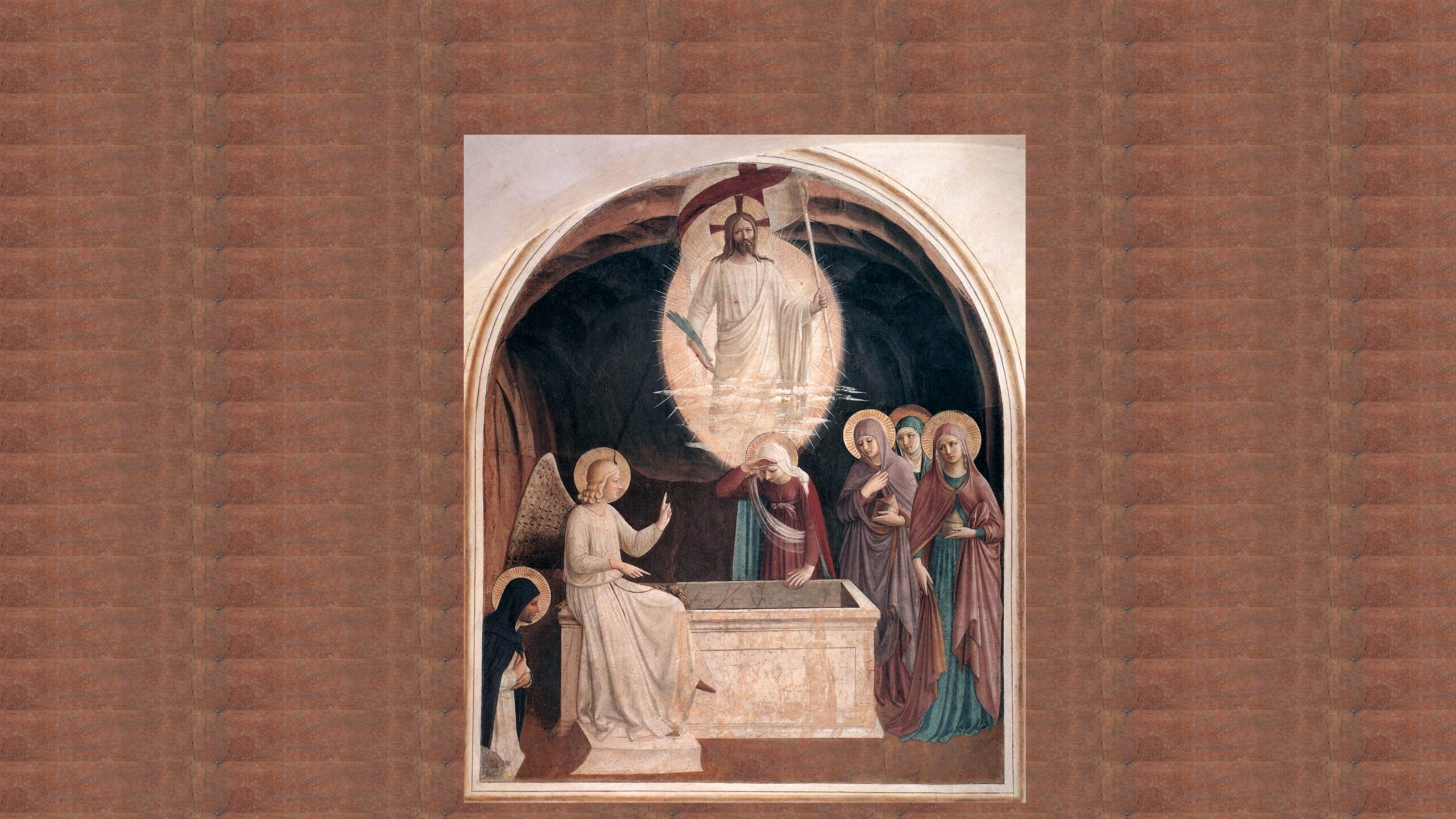

The above apologetic is given its context by a detailed exposition of the fulfilment that the marriage covenant language of the Old Testament finds in the persona of Christ. Here, Levering draws primarily on Brant Pitre’s Jesus the Bridegroom. He offers an overview of the covenantal relationship described by Exodus, the spiritual wedding of the prophets, and the love expressed in the Song of Songs. He traces these themes into the New Testament, to the bridal chamber of the Cross and on to their full accomplishment at the wedding feast of the Lamb, thus convincingly providing a ‘nuptial’ reading of Scripture.

Levering’s contemporary concern comes particularly to the fore in the second chapter, Image of God. The less-controversial, but important, question that threads through this chapter is whether the image of God is found, properly-speaking, within the individual rational soul or within the family community. Levering studies the response of three theologians: Hans Urs von Balthasar, Matthias Joseph Scheeben and Karl Barth. His analyses, particularly of von Balthasar’s thought, delve far enough to draw out important patristic contributions to an understanding of the Trinity, as well as the philosophic influences of Hegel and Buber, amongst others. Levering essentially ends by upholding von Balthasar’s delineation of the imago Dei as best equated with the conjugal analogy, whilst avoiding a direct correlation of the Trinitarian persons with the different members of the family community. The avoidance of a strictly physical application of the analogy allows von Balthasar, and Levering with him, to see the Trinity most fully imaged in the self-giving fruitfulness of the spouses, which is carefully distinguished as being spiritual as much as bodily[5].

The specific question of the first male-female community is returned to in the third chapter on Original Sin. Levering outlines a fairly straightforward comparison between three modern authors (Arnold, Reno and Cotter) and three Fathers of the 4th-5th centuries (Ephraim, Chrysostom and Augustine). Whilst he finds a certain sensibility in the moderns for the human being’s community-dynamic, the marital dynamic and context of Original Sin is more directly addressed by the Fathers. St John Chrysostom’s emphasis on the spouse as the greatest of the creaturely gifts to man, and the consequences of pride within this relationship for relations with the Divine and other humans, are particularly interesting.

In addressing the place of Christ’s Cross within marriage, the following chapter is perhaps of special relevance for anyone involved in marriage preparation. Drawing from Reformed pastor Timothy Keller, Levering boldly challenges the “sinful self-centredness” that is “the main enemy of marriage”[6]. He considers this to be responsible for the contemporary shift in the way marriage is seen: from something that is transcendentally-orientated to a matter of self-realisation. Against this, he delivers a thorough explication of the sacrificial nature of marriage and the participation of conjugal love with that of Christ crucified. Levering turns to a late medieval figure, St Catherine of Siena, drawing extensively from her letters to illuminate the mystical union with Christ that she retains equally valid for married couples as for religious. Levering traces this notion back to Ephesians 5, to reflect on the nature of Christ’s love for the Church, before examining Karol Wojtyła’s philosophical analysis of love and the gift of self.

In his introduction, Levering notes the inter-relatedness of the final three chapters, commenting that “there is a relationship between recognising procreation as the primary ‘end’ of marriage (chapter 5), valuing marriage as a sacrament at least in some sense (chapter 6), and perceiving marriage’s powerful contribution to social justice (chapter 7).”[7] The underlying and central importance of the question of the procreative end of marriage is emphasised by the comparative length of its chapter. In a sense, this is the pragmatic hinge of the book. The implicit suggestion arises that this constitutes the Church’s and the State’s common point of interest in marriage. It is also the widest-ranging chapter, drawing us from Plato’s thought-experiment around the communal breeding of elite citizens, through various Fathers of the Church, to Pope Pius XI, Dietrich von Hildebrand and Cormac Burke.

Levering’s portrayal of the patristic tradition returns a clear primacy of the good of offspring amongst the ends of marriage. In contrast to this, Levering offers an appraisal of von Hildebrand’s attempt to prioritise mutual love as marriage’s primary meaning, whilst retaining procreation as its primary end, in the 1929 opus On Marriage. Levering critiques this approach, demonstrating the failure in logic that results from bracketing procreation within the conjugal union. Levering understandably criticises von Hildebrand for “abstracting from male-female sexual relations”[8]. However, it is not clear if the author does not simultaneously conflate sexual relations and sexual difference in the criticism: it appears, at least, that von Hildebrand is left without the possibility of viewing the male and female as complementary spiritual types in unity with their complementary sexual difference.

Levering also allows Burke to ‘speak’ his views convincingly regarding the equalisation of the procreative and unitive ends of marriage. Levering logically sums up his dismantling of this position with the insight that the procreative end is only reached with difficulty when prioritising the unitive end, whereas the unitive end follows naturally when starting with the procreative.

In tackling the sacramentality of marriage in Chapter Six, Levering again demonstrates his willingness to allow ‘the other side’ a fair hearing. The core issue is whether the Sacrament of Matrimony was invented by the medieval Church. Reynolds provides the case for, drawing primarily on the pre-twelfth-century absence of a clearly-defined system, and indeed on several patristic writings. Reynolds’ slightly cynical, sociological explanation for the sacramentalisation of marriage during the Gregorian reform and following Peter Lombard is respectfully aired. Levering’s response involves two steps: an exploration of the notion of the development of doctrine, with the aid of Craig Keener’s writings, and a more direct response with the writings of Schillebeeckx. Through the latter’s scriptural exegesis, Levering traces the prophetic and covenantal nature of Old Testament marriage through to Christ’s incontrovertible teaching on indissolubility, drawing the significance of the self-sacrificial surrender of marriage into clear relationship with its eschatological meaning as a sign of Christ’s union with His Church. At the same time Levering offers a convincing historical apologetic for the post-twelfth-century developments in the light of the Church’s concern for the sacrament’s same, spiritual significance and for avoiding its abuse for political or personal ends.

The last chapter – Social Justice – makes a deliberate step into the foray of a more sociologically-inclined, contemporary apologetic for marriage. The ecumenical dimension to Levering’s work is especially clear here, as he opens with the “urban apologetics” of the Evangelical pastor, Christopher Brooks[9]. This first section offers very revealing insights into the impact of instability in the family, and particularly absent fathers, in urban, Afro-American society. Brooks reports over 70% of babies being born into fatherless houses, with a higher-than-average number of men behind bars[10]. This section complements the final part of the chapter, in which Levering turns to further studies, both sociological and on government public policy around marriage and family life issues. He draws from these the acute observation that inequality most clearly arises from women’s tendency to seek children, regardless of their marital state, and of men’s to not do so unless married. Together with the vicious circle of government spending on contraception, its correlation with the number of children outside of a marital union, and the correlation of the latter with poverty, Levering provides a resounding response to the critics of Christian marriage that he presents earlier in the chapter. He concludes that a “marriage revolution” is indeed needed[11], and proposes Brooks’ five pillars for a family life that is capable of underwriting a just society[12].

It should be evident from the above that Levering has produced a volume rich in breadth, in source material and in themes. Notwithstanding the slightly different structure and approach, each chapter achieves three things: a retrieval of important source material; an engagement with contemporary theology (critics included); and a clear endpoint for earthly marriage as an image of the mystical marriage. The book’s clear, eschatological focus is a powerful and needed reminder in the face of a loss of faith, and its content an invaluable resource. Thanks also to the author’s fluidity and clarity of writing, the often-dense content of Engaging the Doctrine of Marriage is delivered in a remarkably easily-readable manner.

If there is one criticism to be made, the book’s breadth of themes and its focus on the mystical marriage results in a slight loss of a sense of connection between the themes, especially around the relationship of man’s sexual nature to his imaging of the Creator. It seems ironic to note this, as the weighty fifth chapter expounds with great clarity the primacy of the procreative end of marriage.

In touching briefly on Pope John Paul II’s emphasis on the Trinity as model of the family, Levering admits his unconcern for the lack of acceptance that this analogy has found in some quarters at the end of the second chapter. He argues his position by holding that “the man-woman relationship can still retain significance” for the imago Dei “even if the image of God is found in the soul rather than strictly in the man and woman”[13]. Whilst this position is entirely coherent, it also appears to stop short of the very contemporary debate around the nature and meaning of masculinity and femininity. Levering observes that, to be “in the image of the triune God – involves being in relational communion. There is no human ‘image of God’ abstracted from the relational call of God who made us to know and love him by becoming ‘the Bride, the wife of the Lamb’.”[14] As his conclusion to Chapter Two, this statement appears to pass by the physical nature of the sexual difference, whilst unavoidably revealing that the eschatological marriage that we are concerned with itself rests on the language of sexual difference. The essential nature of the masculine and feminine in relation to the Trinitarian image is only substantially addressed through the lens of von Balthasar.

Given the above, the affirmation of the image of God primarily as “self-surrendering fruitfulness”[15], and the presentation of marriage, religious celibacy and singleness as apparently equally alternative possibilities for living out this imagery[16], create the possibility for the reader to not attribute the necessary theological weight to the specificity of the gift of one’s sexual nature, involved as it is in the total gift of self (body and soul) in marriage and, equally, in religious life. As a result, it is not entirely clear how a formal consecration of self, in the sacraments of matrimony and priesthood or through religious vows, with their activation of or positive abstinence from sexual activity, relate to the eschatological marriage over and above the single (and indeed celibate) life.

Nonetheless, the book clearly and ably presents the fact that, in the words of Scheeben, “Christian marriage… has a real, essential, and intrinsic reference to the mystery of Christ’s union with His Church. It is rooted in this mystery… and so partakes of its nature and mysterious character”[17]. The only shortcoming would be the slightly under-elaborated relationship of sexuality and procreation to this mystery.

[1] M. Levering, Engaging the Doctrine of Marriage, Cascade Books, Eugene, OR, 2019, p. x.

[2] Cf. Levering, p. 2.

[3] Baumann, Love and Violence, p. 195 in Levering, p. 47.

[4] Keefe, Woman’s Body, p. 210 in Levering, p. 56.

[5] Cf. Levering, p. 70.

[6] T. Keller and K. Keller, The Meaning of Marriage, p. 5, 9 in Levering, p. 114.

[7] Levering, p. 12.

[8] Levering, p. 170.

[9] Cf. Brooks, Urban Apologetics: Why the Gospel is Good News for the City, in Levering, p. 217.

[10] Brooks, p. 18 in Levering, p. 218.

[11] Coontz, Marriage, a History, p. 308 in Levering, p. 246.

[12] Brooks, p. 99 in Levering, p. 220.

[13] Levering, p. 84.

[14] Levering, p. 88.

[15] Levering, p. 64.

[16] Cf. Levering,p. 247, 254.

[17] Scheeben, The Mysteries of Christianity, p. 601 in Levering, p. 252.

Share this article

About Us

The Veritas Amoris Project focuses on the truth of love as a key to understanding the mystery of God, the human person and the world, convinced that this perspective provides an integral and fruitful pastoral approach.