Regarding the response of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith on the possibility of blessing same-sex unions

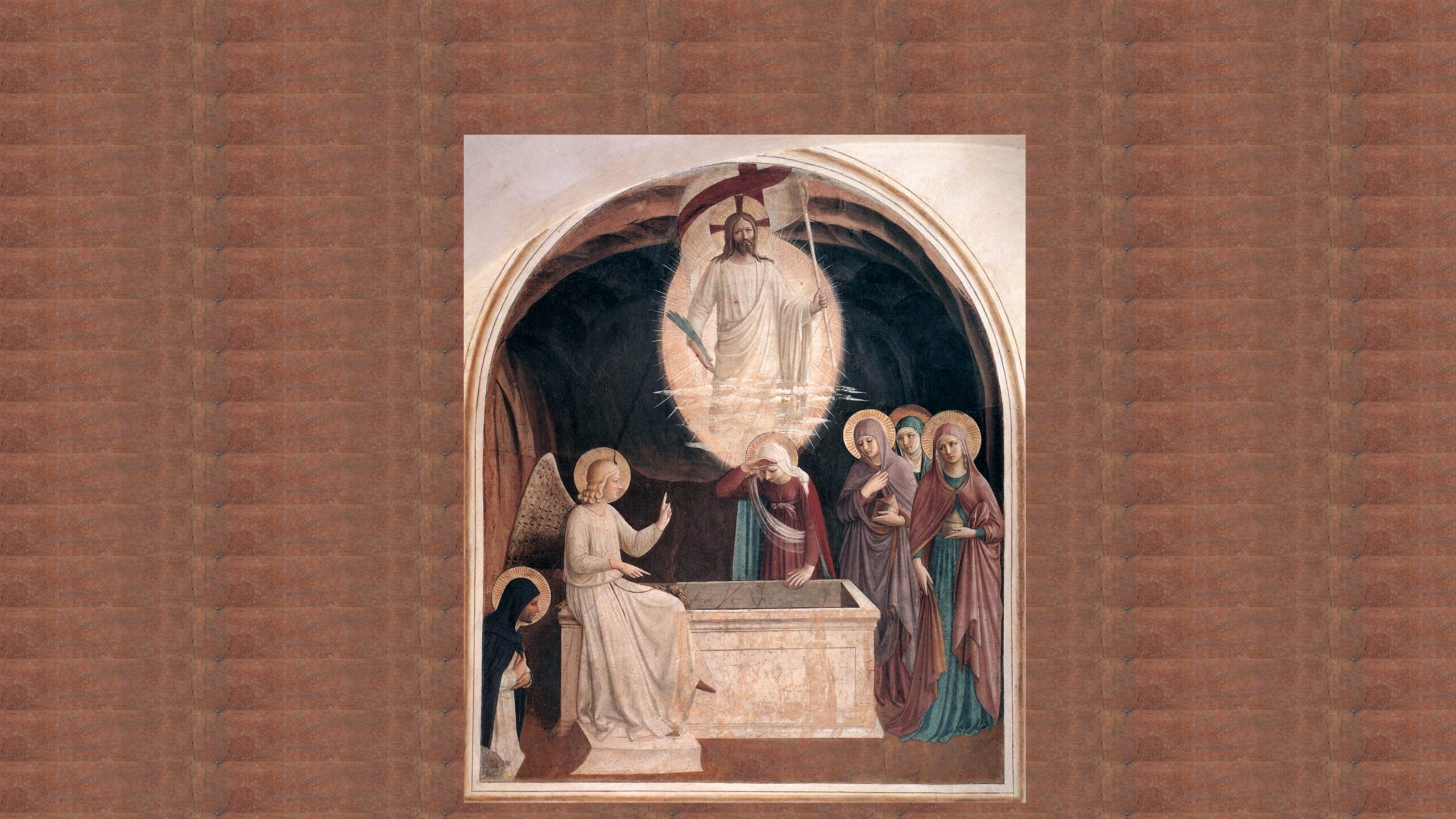

When Jesus rose from the dead, he offered his sacrifice of praise or blessing to the Father. And then he ascended into heaven, blessing his Disciples (Lk 24:50). In this way, Easter recapitulates the whole of creation, given that in the creation account of Genesis, too, God concludes his work with a blessing (Gen 1:28). God blesses, that is, he enables his work to receive the fruitfulness of the living water that flows from him. He thus declares that he will be present and active in creation week by week, month by month, year by year. Then, in the fullness of time, the Church emerges as the space opened up by the glorious Christ, so that this created fruitfulness will never end, and in this space, it will be possible to generate, not only the life of this earth, but the fullness of life everlasting.

At the end of last February, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith responded to the question about the possibility of blessing unions between persons of the same sex. It is not surprising that it responded in the negative—the mere doubt would have been scandalous only two or three decades ago. What is surprising is the openly contrary reaction the Congregation’s response has received in the Church. Theologians, associations, magazines, even a cardinal, have considered the answer to be erroneous and think that it will soon have to be changed. How grave is this situation?

To answer this question, it is necessary, first of all, to go back to the foundation. Blessing, I said, has to do with the Father’s creative plan. The book of Genesis associates the blessing with the culmination of the divine work, forming man and woman and calling them to become one flesh. From this union the child is born, the culmination of divine blessing, from which the whole history of salvation is then narrated, looking forward to the hope of the Messiah. Every blessing of God, old and new, therefore, passes through the acceptance of the language of the difference between male and female. Accepting this language, which men and women have not created, they open themselves to the presence and action of the Creator in their lives.

Some types of union between man and woman, such as adultery or polygamy, deviate from the order of creation. In such unions, the relationship between man and woman is not suited to receive the divine blessing. They lack structural elements to guard love and to transmit life with dignity. This structure is all the more lacking in the stable same-sex union, which claims to be comparable to marriage. The constitutive role of the man-woman relationship itself is now denied, thus opposing God’s original plan. Therefore, according to St. Paul, justifying homosexual acts is a consequence of denying the visibility of God in his created work (Rom 1:18-32).

And thus we understand what is at stake in this debate. First of all, the profession of God as Creator is at stake. The idea is spreading today that one’s sexual inclination is a gift from God, who loves us as we are. God thus stays at the origin of one’s feelings, but he is no longer at the origin of one’s body, with its sexual differentiation. God’s presence is thus denied in the exteriority of the body, that is, in the body’s capacity to put us in relation to others, beyond ourselves. But if God is alien to this sphere of the person, then he is a God who cannot give unity to the world; then he cannot be the Creator of this world. In this case, if God can act at all, he can act only in the intimacy of one’s feelings, but not in the relationships that take us out of ourselves and weave together our common life.

Thus, a second element comes to light: the relational condition of the human person, who is born of love and is called to the gift of self. Let us note that, as an argument against the response given by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, some critics object that God can bless the positive elements of same-sex unions. They forget that the relationship’s elements are part of a whole, and that the value of each part is judged according to that whole. In a dilapidated house there are many positive elements, but you can no more inhabit it than you can sail a ship that is taking on water. Other critics claim that blessing same-sex unions is possible, because they may be on a path toward conversion, and God’s blessing helps them move toward it. But in this case, it is the persons who can be on a path to conversion (and of these the Congregation refers at all times with sensitivity and respect), it is not the union itself nor the homosexual practice, whose dynamism is not oriented to sexual difference, but to its negation.

These objections are made from the standpoint of individualism. They do not understand that the Creator has not only created individuals, but also a fruitful order of relationships among them. It is the condition of the person as a relational being that gives sexuality its mystery and its direction. Sexuality touches the depths of the person, because from it our life comes, and in it the capacity to give life to others opens up. This view of sexuality implies understanding the person from his or her origin, as someone who has received himself or herself from others; and also from his or her capacity to generate life in others. To rob sexuality of this sense is to promote a human being whose origin is in him- or herself, a human being who is self-generating and incapable of prolonging in others his or her own future.

Finally, faith in the Incarnation of the Word is also at stake. Some think that the Church’s insistence on issues of sexuality is a stumbling block to evangelization. But evangelization either passes through the flesh of persons, or it does not evangelize Jesus Christ, the Word Incarnate. The Lord has assumed our flesh, transmitted from generation to generation, and has recovered its original language. If the sexually differentiated flesh did not have the capacity to unite us so deeply with one another and with God, the Son of God, by assuming the flesh, would not have been able to assume our life; nor would he have been able to transform the flesh so that it could transmit salvation to us. According to the ancient Patristic and medieval tradition, Adam and Eve already professed in a certain way their faith in the Incarnation, precisely by their union in one flesh. For in their union, they experienced the opening of their spousal promise to the fullness of communion with each other and with the Creator.

The stakes are therefore high: the involvement of the Creator in human life, the definition of the human person on the basis of the Creator’s gifts and promises, and the profession of Christ as the one who brings all that is human to its fullness.

But in the face of this great threat, the Easter season gives us as an antidote a great hope, which is born precisely from the blessing of the Risen One. The nuptial blessing, says the liturgy, is the only blessing that was not abolished after sin. The Risen One takes this blessing up again and magnifies it by rising in his true flesh. For this reason, he can institute the sacrament of marriage, one of the pillars of the Church, and he can also open the way to virginity, which anticipates the fullness of the body in God himself. We can conclude that what is at stake in this debate is Christian hope itself, which passes through the generative capacity of the flesh. Today the Church and society need this hope more than ever. Knowing the menaces that would arise against the faith in the redemption of the flesh, Jesus told us: “Do not let your hearts be troubled” (Jn 14:27). Thus, until the end of time, the voice of the Bride, speaking with the Spirit, will resound, calling the Bridegroom: “Come!” (Rev 22:17). In the meantime, the Church has the mission of confirming in this hope all persons and families whom the Lord calls into her bosom.

Share this article

About Us

The Veritas Amoris Project focuses on the truth of love as a key to understanding the mystery of God, the human person and the world, convinced that this perspective provides an integral and fruitful pastoral approach.